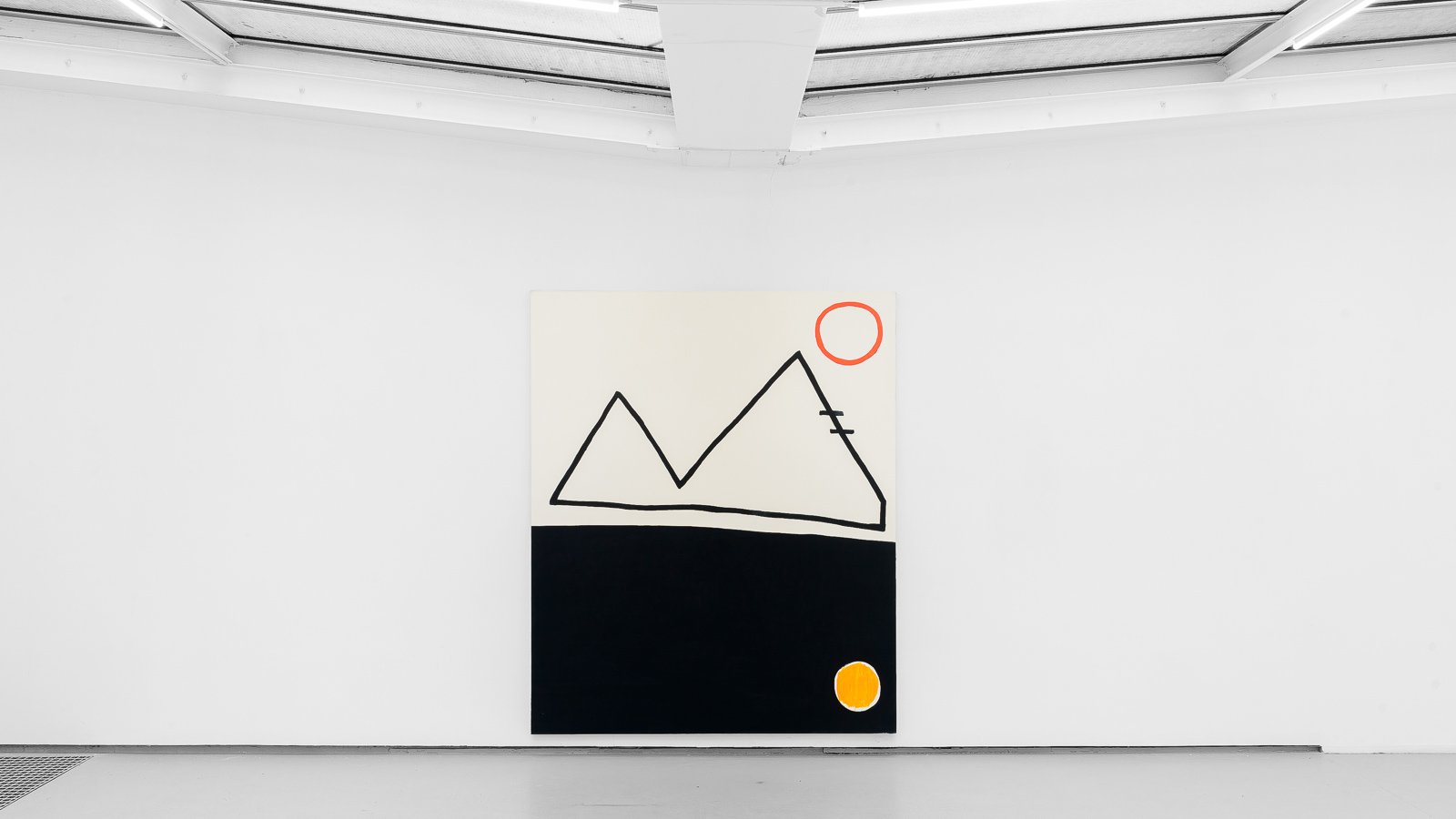

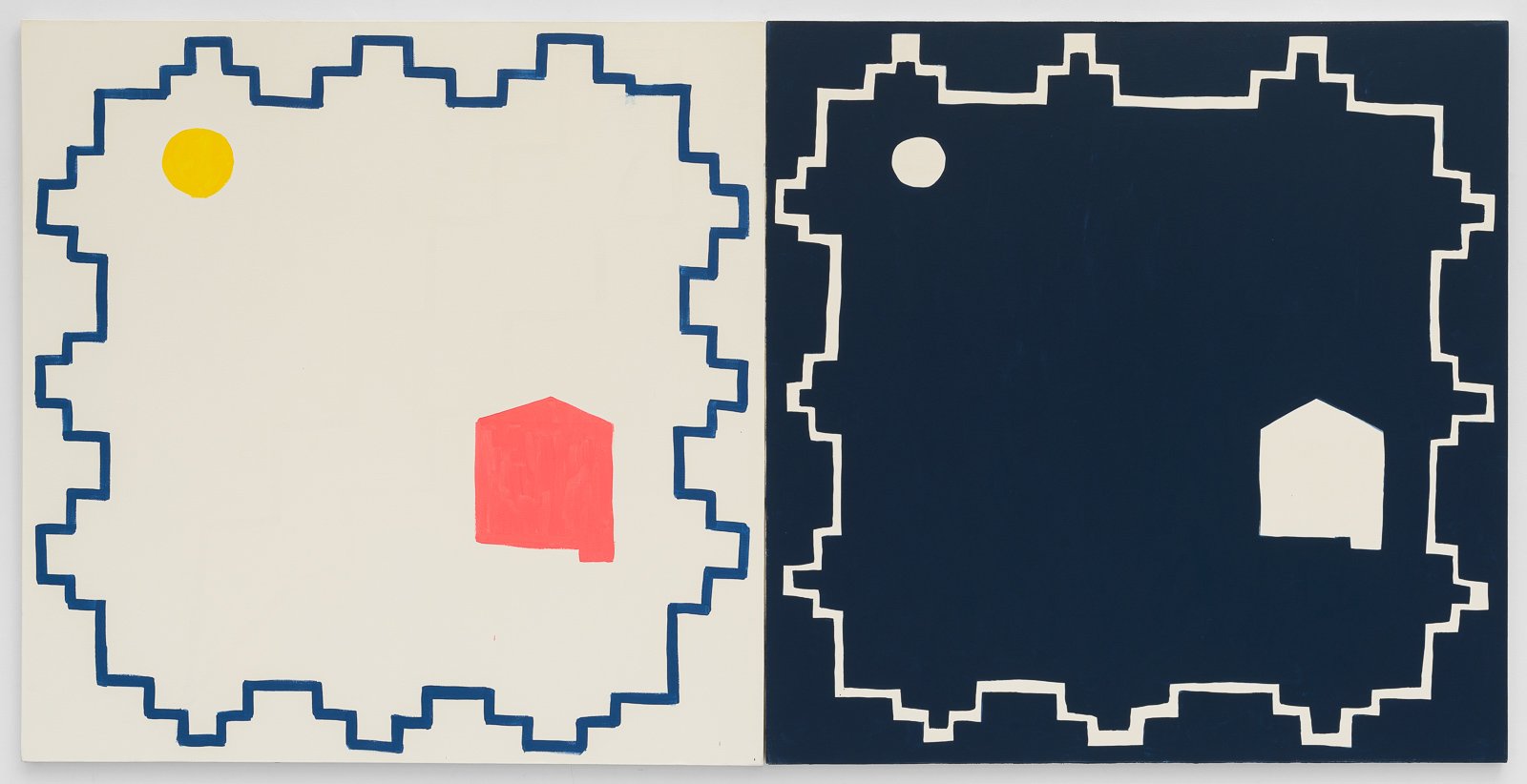

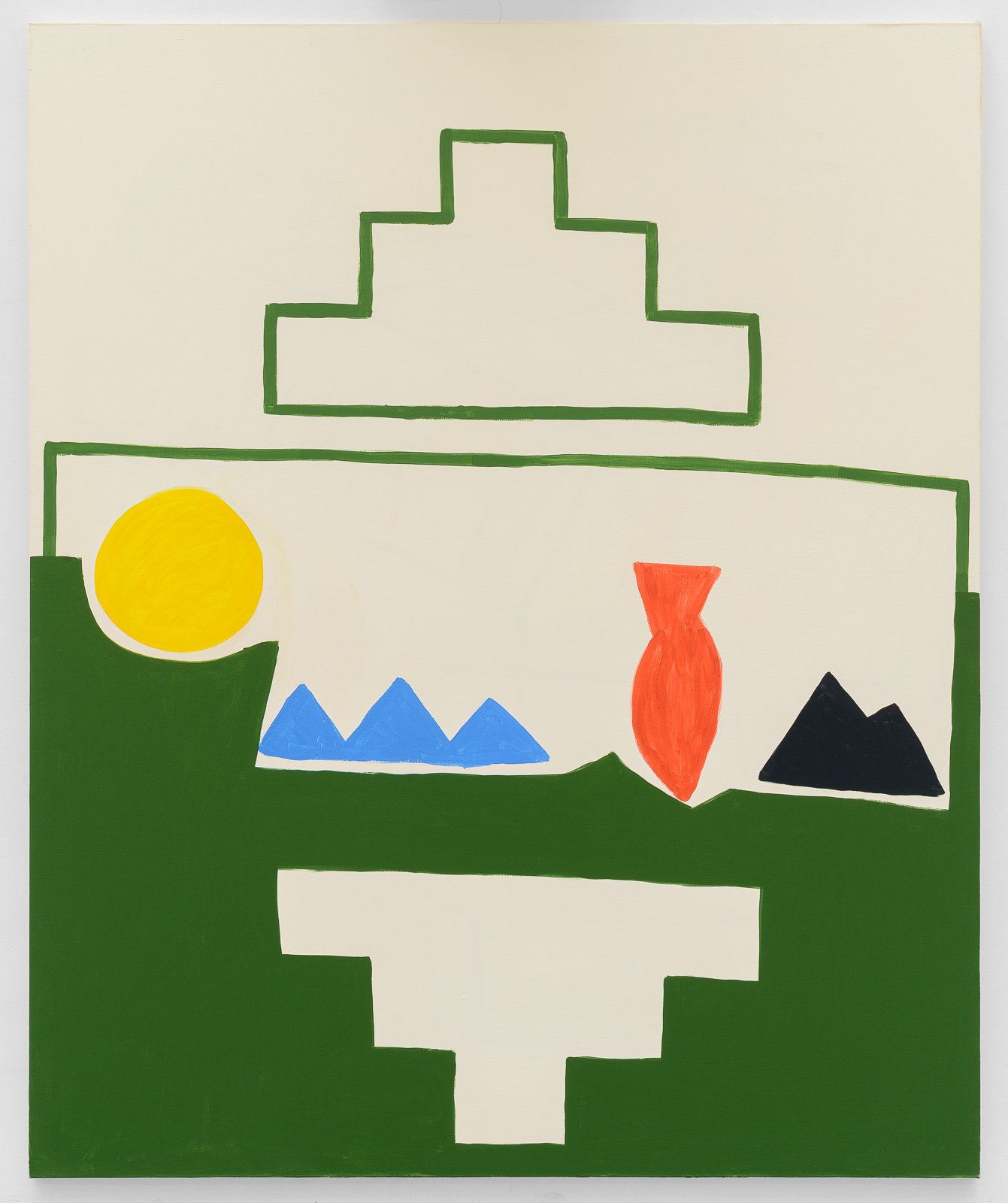

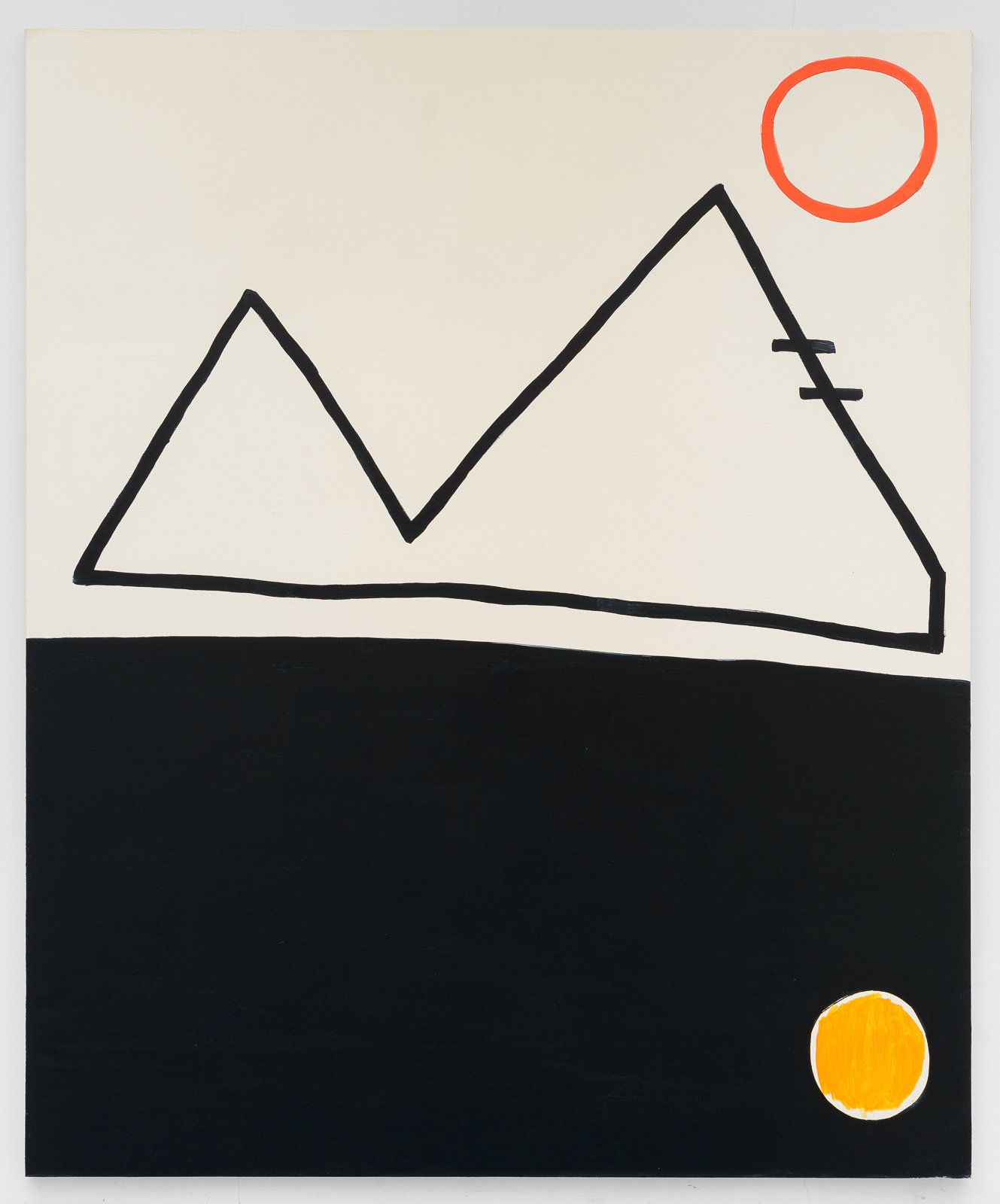

La peinture doit-elle encore avoir un sujet ? Dans ses expositions précédentes à la galerie Valentin ou au Mamco à Genève, les œuvres de Stephen Felton faisaient référence à ses lectures de Moby Dick (It’s a Whale, en 2014) ou de Scènes de la vie d’un faune d’Arno Schmidt (The Wind, Love and other Disappointments, en 2015). Pour cette nouvelle exposition, l’artiste semble piocher dans son vocabulaire des éléments de langage qu’il associe librement pour composer les tableaux, un peu à la manière de Picasso et Braque dans la période dite « synthétique » du cubisme. Un système binaire se met en place : le jour et la nuit, le soleil et la lune, la maison et le jardin, le plein et le vide... Mais cette fois les éléments contradictoires tentent de cohabiter à l’intérieur du rectangle, par symétrie ou dissymétrie, et le poisson se retrouve à voler au milieu des montagnes, comme dans les peintures de paysage à l’encre « Shanshui » de l’art classique chinois.

La peinture de paysage Shanshui (montagne-eau) n’est pas un art sur le motif et n’a vraiment rien à voir avec l’impressionnisme. Il s’agit plutôt d’un maniérisme qui évoque picturalement la nature comme analogie d’un état intérieur, régi par des principes de composition rigides et utilisant des techniques de représentation bien rodées. Le but de ce genre de peinture était de paraître le plus spontané possible, même si l’œuvre finale avait nécessité de nombreux travaux préparatoires. Mais au fond, quelle différence y a-t-il entre la spontanéité et l’imitation de la spontanéité ?

Dans l’art d’aujourd’hui, les phénomènes de rapprochements picturaux semblent de plus en plus présent. Sur Instagram, la peinture a parfois l’air d’avoir été générée par une intelligence artificielle, un peu à la manière du phénomène collectif, tant artistique que commercial, qui a vu se multiplier les expositions cubistes au début du siècle dernier. On pourrait presque parler de random-abstraction (ou de random-figuration), tant certaines œuvres semblent interchangeables. Pourtant, il me semble qu’il en a toujours été ainsi. De la Renaissance aux différents mouvements d’avant-garde, l’art est une production collective. Si des individus ont cherché à se démarquer, ils ont la plupart du temps produit autour d’eux des avatars ou des successeurs qui ont de toute façon banalisé et collectivisé ce qu’il pouvait y avoir de singulier chez eux. Isidore Ducasse a écrit que « la poésie doit être faite par tous », et il semblerait que le nivellement des productions actuelles réalise en partie ce programme anti-romantique, exposé à la fin du 19ème siècle.

Dans son essai Loin de moi, le philosophe Clément Rosset proposait de réviser notre conception de l’identité en suggérant qu’elle serait en réalité constituée d’un collage d’inspirations extérieures, reniant ainsi le dualisme couramment admis de la personne sociale s’opposant au moi profond. Les tableaux de Stephen Felton ont l’air spontané parce qu’ils utilisent des couleurs franches et une forme de dessin à la ligne presque maladroite, enfantine. Pourtant, la conscience que ce vocabulaire possède de sa propre efficacité le place d’emblée dans un langage adulte, fait de références complexes à des idées simples. Si la peinture de Felton est effectivement un langage, on ne sait pas exactement quel en est le sens ni l’usage. Elle se situe dans cette hésitation entre dire et ne pas dire, représenter quelque chose ou présenter l’action de peindre. Mais surtout, il ne s’agit pas d’une démarche purement subjective, comme son apparente spontanéité pourrait le laisser penser. Sa peinture se réfère à des archétypes collectifs et les agence comme des rébus sans solution, des rêves à interpréter ou des poèmes visuels. Elle ne s’adresse pas, comme les peintures de paysage Shanshui, à des lettrés contemporains, mais à tout le monde et à n’importe qui. Elle est, par son intermédiaire, « faite par tous ».

Hugo Pernet

Juillet 2022

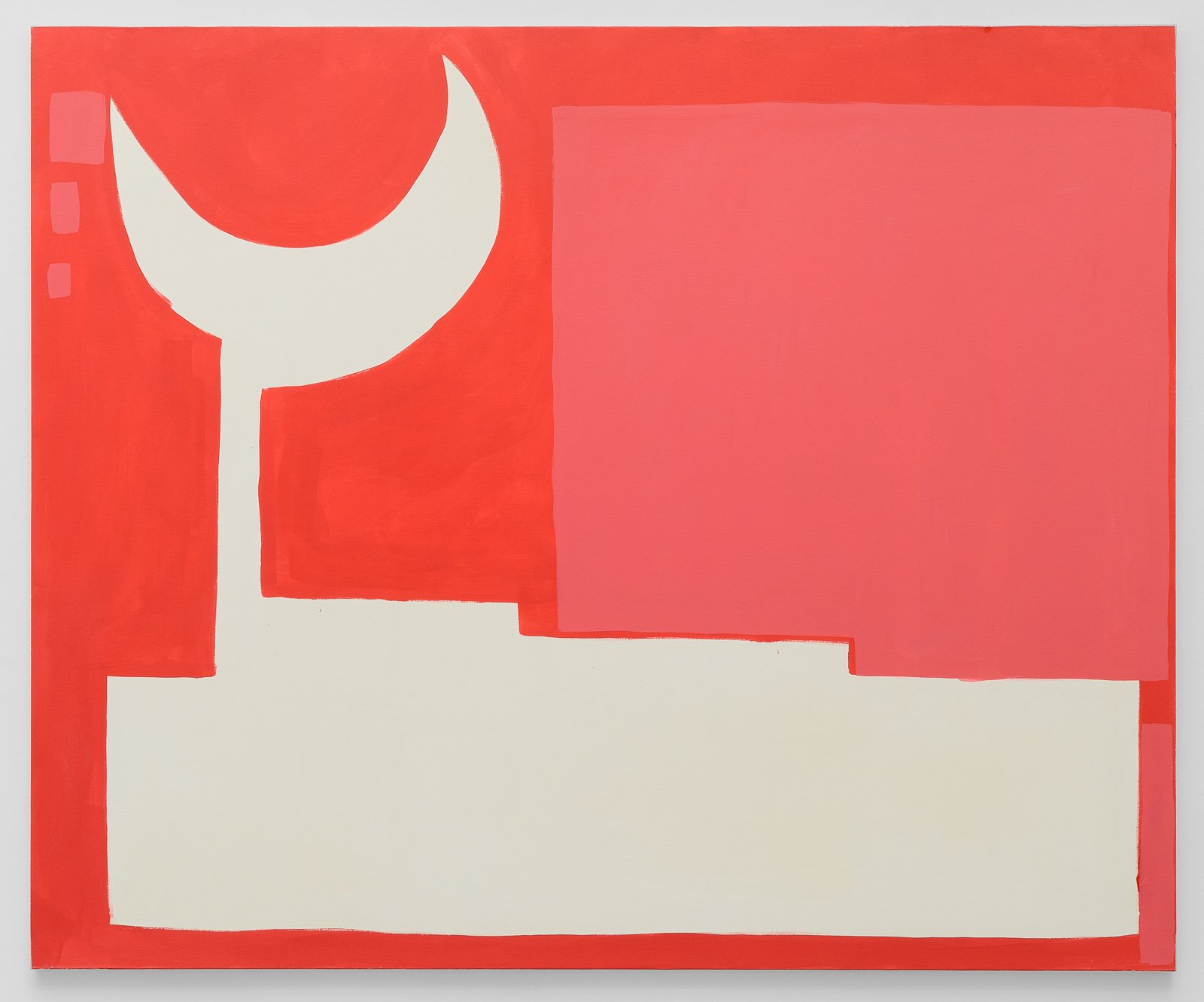

Does painting still have to have a subject? In his previous exhibitions at Galerie Valentin or Mamco in Geneva, Stephen Felton's works referred to his readings of Moby Dick (It's a Whale, in 2014) or Arno Schmidt's Scenes from the Life of a Faun (The Wind, Love and other Disappointments, in 2015). For this new exhibition, the artist seems to draw on his vocabulary of language elements that he freely combines to compose the paintings, a bit like Picasso and Braque in the so-called "synthetic" period of Cubism. A binary system is set up: day and night, sun and moon, house and garden, full and empty... But this time, contradictory elements try to cohabit within the rectangle, by symmetry or dissymmetry, and the fish finds itself flying in the middle of the mountains, as in the landscape paintings in "Shanshui" ink of classical Chinese art.

Shanshui (mountain-water) landscape painting is not a motif art and has nothing to do with impressionism. Rather, it is a mannerism that pictorially evokes nature as an analogy of an inner state, governed by rigid compositional principles and using well-honed representational techniques. This kind of painting aimed to appear as spontaneous as possible, even if the final work required a great deal of preparatory work. But ultimately, what is the difference between spontaneity and the imitation of spontaneity?

In today's art, the phenomena of pictorial approximations seem to be more and more present. On Instagram, painting sometimes looks like it was generated by artificial intelligence, a bit like the collective phenomenon, both artistic and commercial, that saw the proliferation of Cubist exhibitions at the beginning of the last century. One could almost speak of random-abstraction (or random-figuration), so much so that certain works seem interchangeable. Yet, it seems to me that it has always been so. From the Renaissance to the various avant-garde movements, art is a collective production. If individuals have tried to distinguish themselves, they have most of the time produced around them avatars or successors who have in any case trivialized and collectivized what could be singular in them. Isidore Ducasse wrote that "poetry must be made by all", and it would seem that the leveling of the current productions realizes in part this anti-romantic program, exposed at the end of the 19th century.

In his essay "Loin de moi", the philosopher Clément Rosset proposed to revise our conception of identity by suggesting that it would consist of a collage of external inspirations, thus denying the commonly accepted dualism of the social person versus the deep self. Stephen Felton's paintings look spontaneous because they use bold colors and an almost clumsy, childlike line-drawing style. Yet the awareness that this vocabulary has of its efficacy places it at once in an adult language of complex references to simple ideas. If Felton's painting is indeed a language, it is not clear what its meaning or use is. It is situated in this hesitation between saying and not saying, representing something, or presenting the action of painting. But above all, it is not a purely subjective process, as its apparent spontaneity might lead one to believe. His painting refers to collective archetypes and arranges them like rebus without solution, dreams to be interpreted, or visual poems. It is not, like the Shanshui landscape paintings, addressed to contemporary scholars, but to everyone and anyone. It is, through it, "made by all".

Hugo Pernet

July 2022